On this page:

-

What does it mean to be Chinese Canadian?

-

What is Diaspora?

-

-

History of Chinese Canadians in Canada

-

What Does a Head Tax Look Like?

-

The Many Different Immigration Pathways to York Region: A Newfoundland Story

-

-

History of Chinese Canadian in York Region

-

Battle of Hong Kong

-

Kew Dock Yip

-

What does it mean to be Chinese Canadian?

The Chinese community is diverse. While Chinese Canadians share Chinese heritage and have roots in China, they speak a variety of languages and have come to Canada from many different countries. People of Chinese descent have settled all around the world, developing unique cultures and practices that combine their Chinese heritage with their new home countries.

Sung family in front of family home in Markham, 1999. Courtesy of Sung family.

Sung family in front of family home in Markham, 1999. Courtesy of Sung family.

The reasons for people leaving China are varied. Some have left to search for better job opportunities, to enrol in our school system, to escape the unsafe conditions of war, disease, poverty and general unrest. Others have left for environmental reasons, seeking to escape the severe air and water pollution, and benefit from a greater amount of green space. Many migrant men travelled to other countries in search of work opportunities, at times leaving their families behind in China. Some people like Paul Chiang’s family left (China for India) because of the political unrest. Before coming to Canada, Chinese Canadians in York Region have lived in Pakistan, India, Jamaica, Vietnam, China, and many other places and have brought parts of those cultures with them.

People of Chinese heritage can also belong to smaller Chinese subgroups or ethnic minorities. The Hakka community, for example, is a Chinese subgroup from the north of China who have migrated south and to other areas such as India and the Caribbean. Chinese subgroups and ethnic minorities have their own traditions, cultural practices, foods and even languages.

Listen to these community members talk about the diversity of the Chinese diaspora:

History of Chinese Canadians in Canada

In the late 1800s, Canada saw the first of many waves of Chinese immigration. There were several push and pull factors for Chinese immigration to Canada during this time. Experiences of war and poverty in China pushed some to leave China and seek other opportunities. In the early 1850s, the Shuswap (now Secwepemc) nation peoples found gold along the Fraser River, British Columbia. Many Indigenous families mined for gold alongside the Hudson’s Bay Company up until 1857 when word spread of the wealth in the river.

A significant pull towards Canada was as the word of available gold spread - leading to many people of Chinese descent immigrating as part of this gold rush of the Fraser Valley. Hoping to find a better life in the place they called “Gum San” or “Gold Mountain” - the name Gold Mountain,(金山) was the Chinese nickname for places where discoveries of gold sparked opportunity seekers (including California, and British Columbia).

Even after the gold was gone by the 1860s, the name “Gold Mountain” stuck, representing the hopes Chinese immigrants had for wealth and a better life.

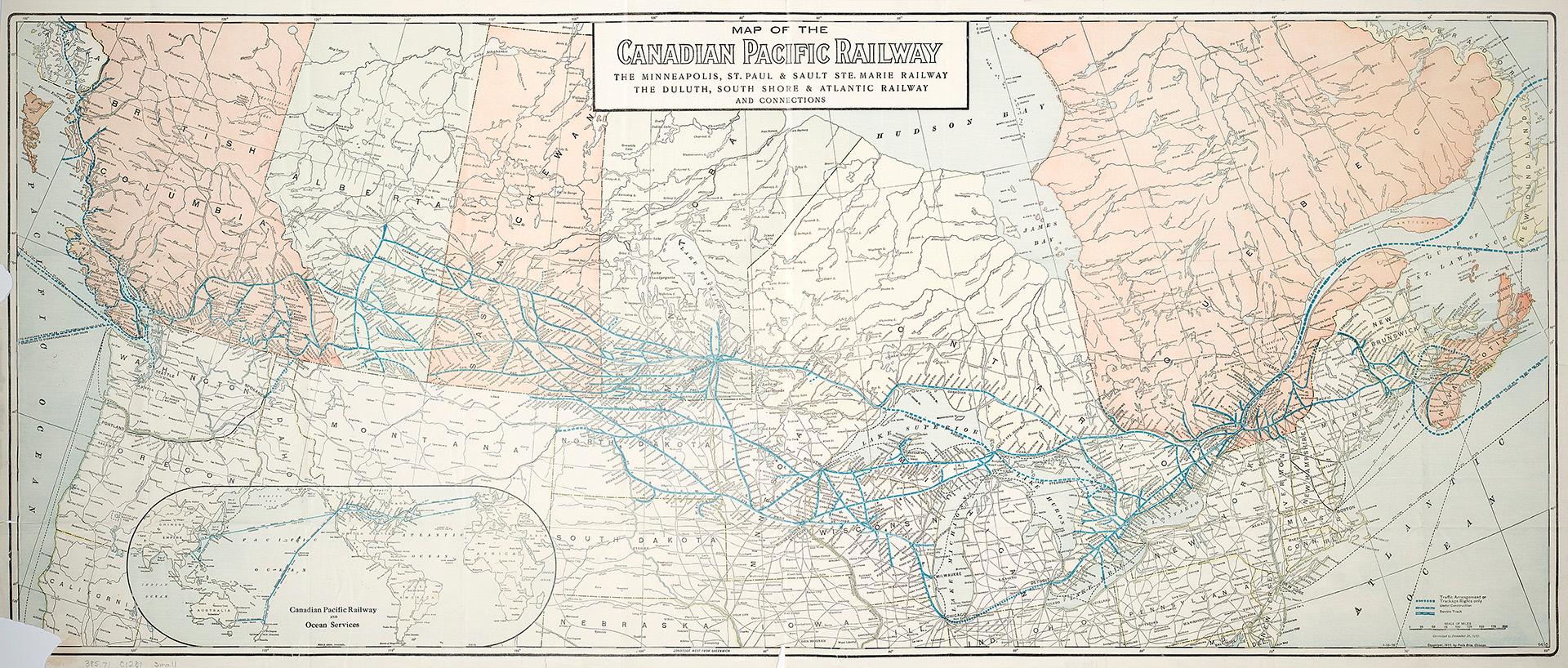

Map of the Canadian Pacific Railway, 1919. 385-71-C1281-SMALL. Toronto Public Library.

Map of the Canadian Pacific Railway, 1919. 385-71-C1281-SMALL. Toronto Public Library.

Chinese workers on speeder, on a bridge over the Thompson River. January 1, 1899 BC Multicultural Photograph Collection at the Vancouver Public Library

Chinese workers on speeder, on a bridge over the Thompson River. January 1, 1899 BC Multicultural Photograph Collection at the Vancouver Public Library

Chinese men came to Canada for work opportunities, including the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, but remained an isolated province. A decision to build the railway through the traditional territories of many Indigenous nations, meant the disruption of a way of life and cultural practices for many communities. Chinese labourers came from China and the United States to build the CPR to unify the country, at the expense of many First Nation communities. Chinese workers were paid less, had to pay for their own food and clothing and were given the most dangerous work with unsafe working conditions. Chinese workers were often treated unfairly by white workers and foremen. Despite the hardworking dedication of the migrant Chinese, those of Asian descent were still subjected to racism and discrimination.

Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885, white Canadians no longer saw a need for cheap labour from Chinese immigrants. On November 7, 1885, the historic “last spike” photograph was taken with CPR officials and railway workers. Not one person in the photograph was Chinese.

Hon. Donald A. Smith driving the last spike to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway. Library and Archives Canada / C-003693.

Hon. Donald A. Smith driving the last spike to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway. Library and Archives Canada / C-003693.

|

Did you know? |

|---|

|

Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial, Toronto The Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial monument in Toronto commemorates and recognizes the contributions of the 17,000 Chinese workers who made Canada’s transcontinental railway possible. Built in 1989, it is located close to the Rogers Centre, beside the railway lines. > Listen to artist Eldon Garnet discuss the creation of this work. |

Upon the completion of the railway, Chinese workers took on other jobs in factories, worked in mines, hand laundries, or opened their own businesses to sustain themselves and their families. They also operated farms, successfully growing vegetables and selling their produce on carts. Often they were only able to obtain low paying jobs. Even so, many Canadians felt as though their ability to secure a job was taken away by Chinese workers. Public pressure pushed for exclusionary rules to control Chinese immigration across Canada.

This led to a series of racist laws to be passed in Canada after the completion of the Railway with the Chinese Immigration Act in 1885. The Act was intended to discourage Chinese immigration to Canada by enforcing a $50 fee, or “head tax”, on each Chinese immigrant. Over the next 15 years, the head tax was increased to $500, which was approximately two years’ wages for a labourer. The head tax separated many families. Chinese men came to Canada for work while their families remained in China because it was too expensive.

Dr. Ken Ng, a community advocate and medical doctor in Markham, was impacted by the Chinese Immigration Act (1885). When he was born in Hong Kong in 1953, his father was living in Canada. Dr. Ng didn’t have the opportunity to meet his father until he first came to Canada in 1965.

I came to Canada on a plane alone with no other adults accompanying me, and I could not speak English. It was a little scary to travel at that time. But it’s still a memorable experience because that was the opportunity for me to meet my parents. I was born in Hong Kong back back in 1953. My father came to Canada even before I was born. The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place at that time. It was difficult for Chinese to immigrate to Canada. A lot of people have to pay taxes to get to Canada. At that time the economic situation wasn’t very good in China after the civil war and WW2."

- Dr. Ken Ng

What Does a Head Tax Certificate Look Like?

The Head Tax slowed immigration dramatically, but many still made their way to Canada. Chinese immigrant workers sometimes took out loans or relied on the community village members to pool funds to pay the tax. Passed into law on 1 July 1923, a new Chinese Immigration Act (better known as the Chinese Exclusion Act) was enforced, ultimately banning Chinese immigration into Canada until 1947. Only a select few were excluded from the ban. In Chinatowns across Canada, instead of celebrating Dominion Day on July 1st, it became known as “Humiliation Day” and many refused to participate in celebrations.

Similar legislation was passed in the United States and the British Colony of Newfoundland, restricting Chinese immigration to North America for many decades. It was not until 1967 that all remaining race and national origin immigration restrictions were removed by the Canadian government.

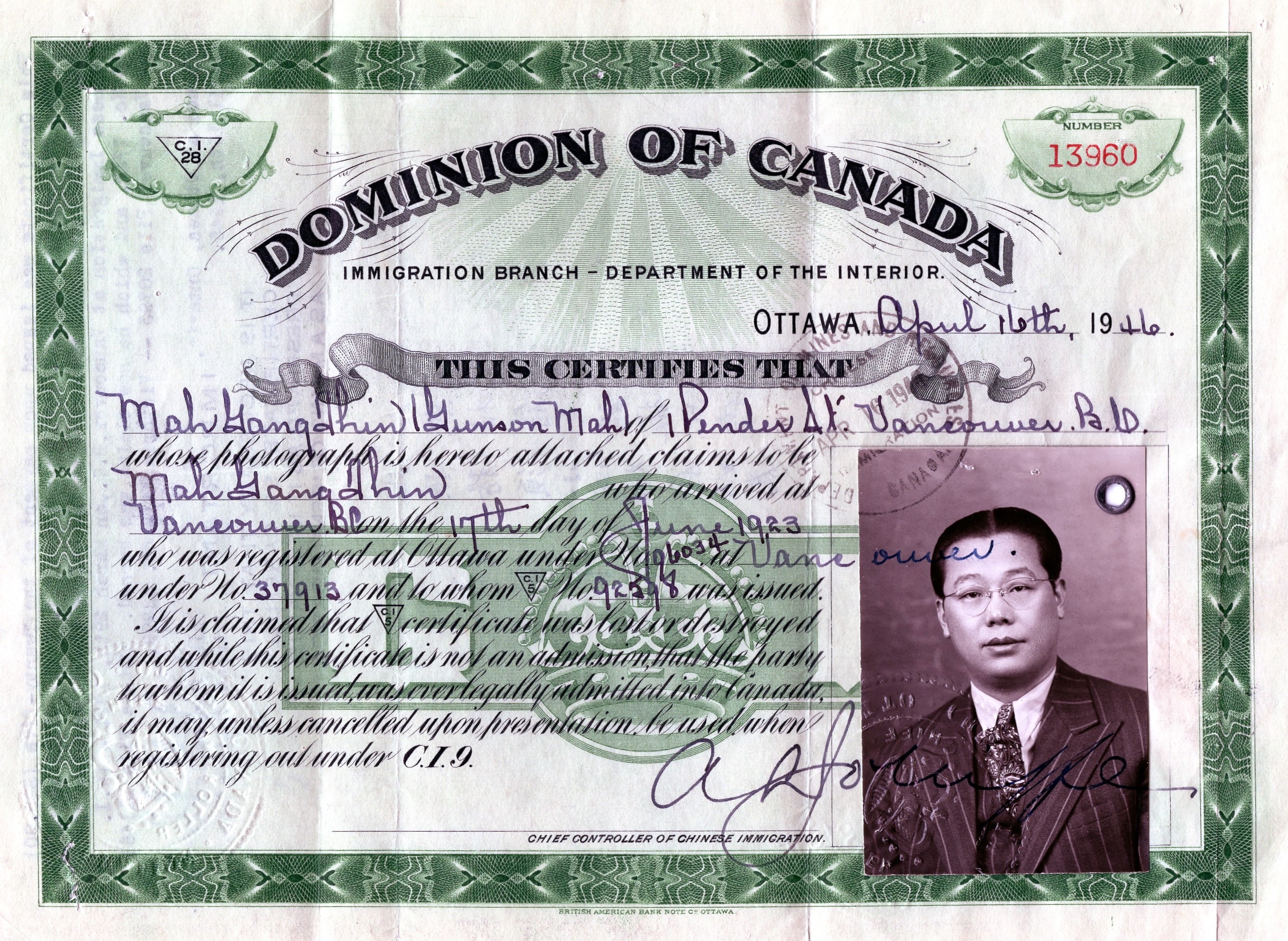

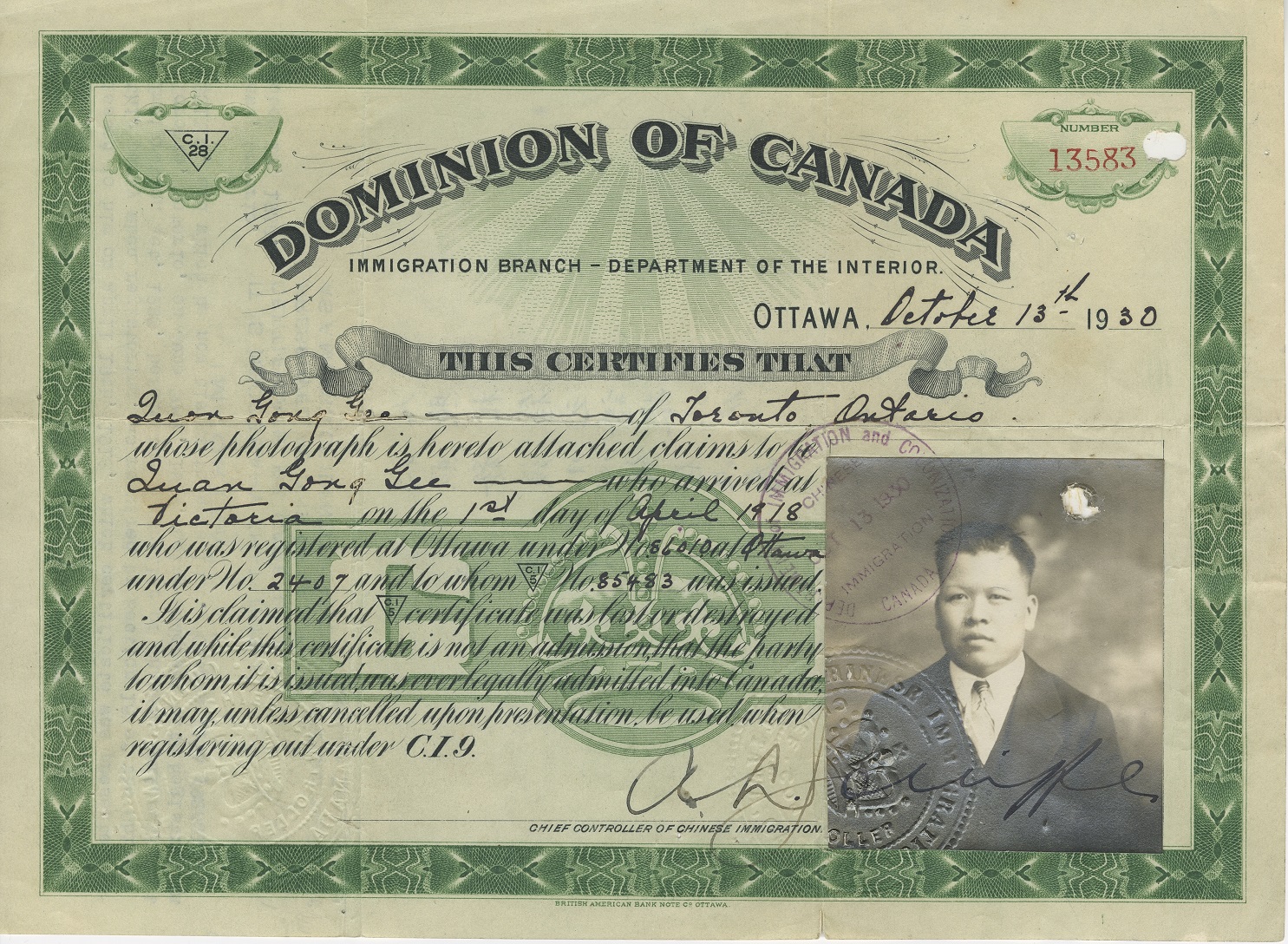

A Canadian Immigration and head tax certificate C.I.9 (replacement). 16 April 1946. It explains on the back of the certificate that he was issued a replacement in 1946 because the original was lost in a fire. Courtesy of the Mah family.

A Canadian Immigration and head tax certificate C.I.9 (replacement). 16 April 1946. It explains on the back of the certificate that he was issued a replacement in 1946 because the original was lost in a fire. Courtesy of the Mah family.

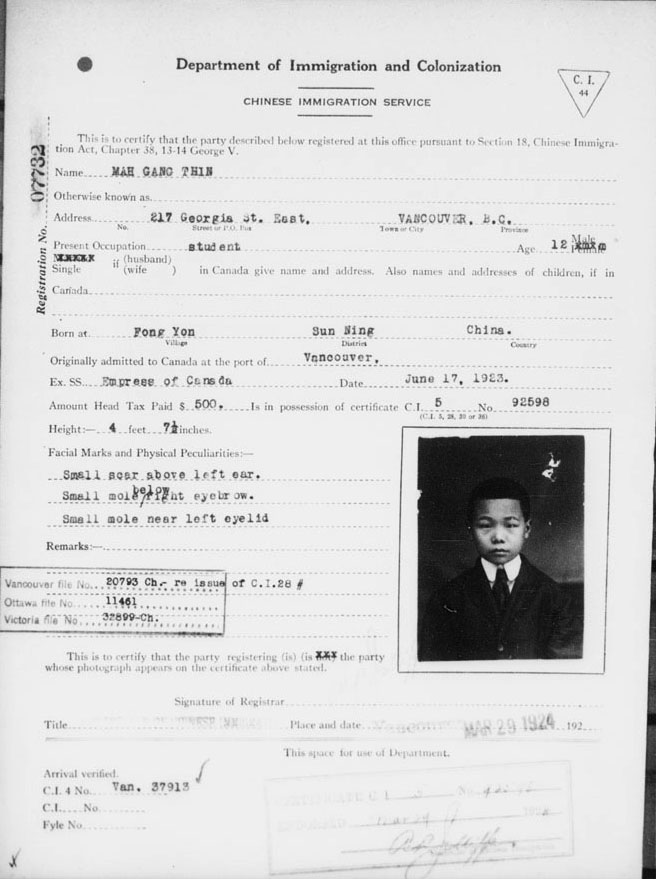

Gunson Mah (Gang Son 更辛) was a Chinese immigrant who came to Canada with his father on 17 of June 1923 when he was 12 years old. His family paid $500 for his admittance to Canada. He lived in Vancouver with his uncle who owned a laundromat. In 1931, Gunson returned to China to marry his wife, Mei, who was unable to move to Canada until 1958. While he waited to be reunited with his wife, he moved to Edmonton and worked as a chef in restaurants during the 1950s and 60s. He later operated a convenience store until 1974.

Government Immigration certificate, 29 March 1924. Courtesy of Mah family.

Government Immigration certificate, 29 March 1924. Courtesy of Mah family.

|

Gunson Mah, 1935? Courtesy of Mah family.

Gunson Mah, 1935? Courtesy of Mah family.

|

Similar Chinese exclusionary legislation was passed concurrently in the United States and the British Colony of Newfoundland, restricting Chinese immigration to North America for many decades. Other countries like Australia also had exclusion laws aimed at Chinese people. For many years, Canada demonstrated in its exclusionary policies that those of Chinese descent did not belong. While the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, it was not until 1967 that all remaining race and national origin immigration restrictions were removed by the Canadian government.

Want to learn more about C.I. certificates? Take a look at this community archive project, 1923 Chinese Exclusion.

The Many Different Immigration Pathways to York Region: The Quan Family

Peter and Lai Shing Quan are amongst the first modern Chinese Canadian families who settled in Markham in 1956. They raised their seven children in Unionville, and many of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren still live and work here today.

Peter’s father and grandfather, and Lai Shing’s father, grandfather and great uncles all came to Canada seeking opportunity. Subsequently, their families were impacted by Canada’s racist policies of Head Tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Replacement Certificate for Gong Yee Quan. Arrived in 1918. Courtesy of Quan family.

Replacement Certificate for Gong Yee Quan. Arrived in 1918. Courtesy of Quan family.

Peter, originally from Hoiping China, arrived in 1951 and travelled across Canada alone to join his father in the family’s laundry business in Oshawa, Ontario. At the age of 17, he worked for $1 an hour in a Whitby canning factory, with a goal of working 100 hours a week. Within 3 months, he had the $400 that he would later use for the down payment to buy the building in which his father ran the laundry business. Today this same location houses the Oshawa Quan Appliance store.

Quan's Laundry operated out of 191 King Street West, Oshawa. The same location now houses the Oshawa Quan TV & Appliance store. Courtesy of Quan family.

Quan's Laundry operated out of 191 King Street West, Oshawa. The same location now houses the Oshawa Quan TV & Appliance store. Courtesy of Quan family.

Lai Shing, originally from Taishan, China, arrived in 1951 with her mother and brother. They joined their father, John Tang Way Mark, the owner of National Cafe in Milton, Ontario. Their family had been separated for nearly 17 years due to systemic barriers created by the Exclusion Act.

With the support of their parents, Peter and Lai Shing were able to purchase a café in Unionville (now part of Markham) which they named Peter’s Restaurant. Although the community was small in 1956 with approximately 400 residents, their business was a success with many locals and tourists travelling Highway 7 stopping for a mixture of Western and later Chinese Canadian cuisine.

Lai Shing Quan walking down Unionville Main Street in winter, 1950s. Courtesy of Quan family. |

Members of the Quan family standing outside of Peter's Restaurant on Highway 7, Markham in the 1960s. This same building now houses Quan TV & Appliances. Courtesy of Quan family.

Members of the Quan family standing outside of Peter's Restaurant on Highway 7, Markham in the 1960s. This same building now houses Quan TV & Appliances. Courtesy of Quan family.

|

In 1958 the Quan family purchased the building and in 1969, they closed the restaurant and opened the original Quan TV & Appliance storefront. Today, the appliance business and property ownership and development form the core of the family’s local enterprises.

At times it can be difficult to believe that the family business that is still owned and operated by my family all started from a small family diner. Now working in the family business that my grandparents started over 50 years ago, I now see it as a true privilege that my grandparents have afforded me.

- Scott Quan

The Quan family is actively involved in the local Quan Association, a benevolent organisation that promotes heritage, culture, camaraderie and educational achievement. In addition, Peter and Lai Shing’s goodwill has contributed to the settlement of extended families, and the building of schooling opportunities locally and in China.

Peter and Lai Shing instilled in their family two important values – to work hard and value education. This has led to not only successful businesses, but has enabled future generations to confidently pursue their personal and professional goals.

Over the years I have invested in York Region because it is a helpful, friendly, safe place for my family.’

- Peter Quan

The Many Different Immigration Pathways to York Region: A Newfoundland Story

Canadians of Chinese descent have arrived in York Region through many different pathways. Interesting is the story of Newfoundlanders of Chinese descent, as it was a separate British colony until 1949.

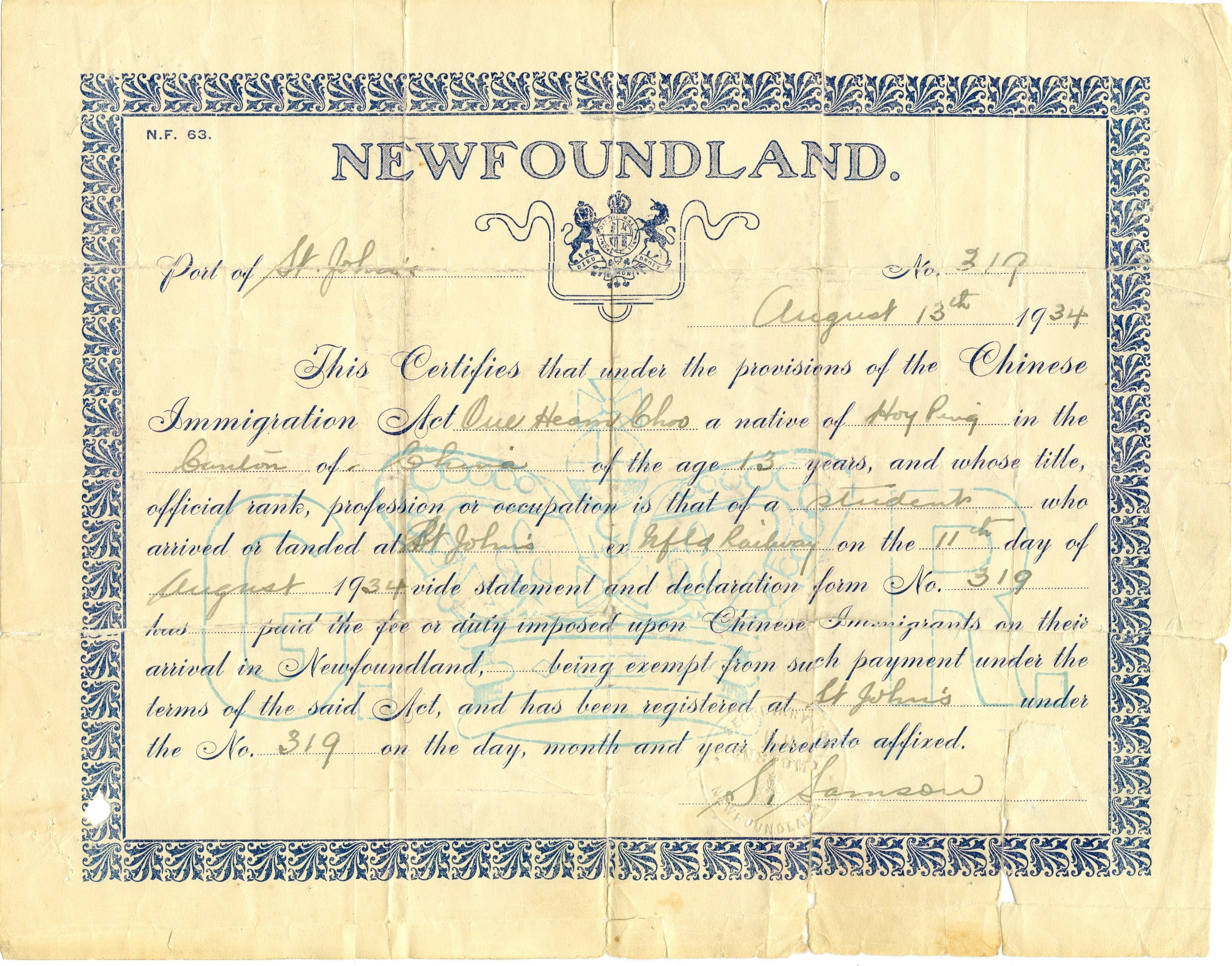

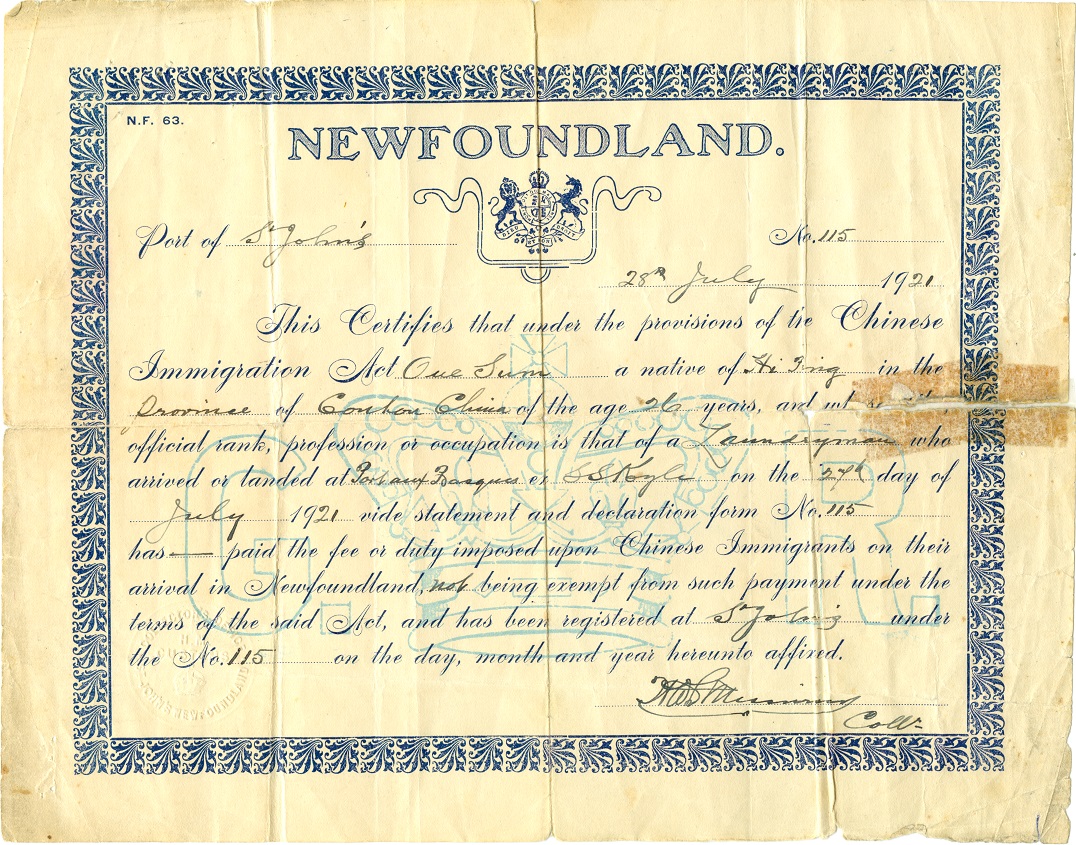

The Aue family has deep Newfoundland and Canadian roots. Hamme Chow Aue, came to Newfoundland in 1934 at 13 years old. He was sponsored by his uncle, Sum Aue, who operated a Chinese laundry in St. John’s, Newfoundland. At that time, Newfoundland was not part of Canada at the time but had passed the “Act Respecting the Immigration of Chinese Persons” in 1906, which enforced a $300 head tax for each Chinese person entering Newfoundland. This tax remained in effect until Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation in 1949.

Newfoundland Head tax certificate of Hamme Chow Aue, 1934 (also known as Oue Heam Choo) Courtesy of Rita Tam.

Newfoundland Head tax certificate of Hamme Chow Aue, 1934 (also known as Oue Heam Choo) Courtesy of Rita Tam. Newfoundland Head tax certificate of Sum Aue, 1921 (also known as Oue Sum or Sam). Courtesy of Rita Tam.

Newfoundland Head tax certificate of Sum Aue, 1921 (also known as Oue Sum or Sam). Courtesy of Rita Tam.Sum Aue was from the Hoi Ping/Kaiping town of Guangdong, China. He was a “married bachelor”, whose wife remained in China and they never had children. He arrived in Port aux Basque in 1921 at the age of 26 years old. He maintained his laundry business until 1969, when he closed and sold the laundry. Hamme was escorted from China, through San Francisco up to Vancouver and then by rail to St. John’s. After arriving in Newfoundland, Hamme worked at his uncle’s laundry before opening his own restaurant.

Even though my dad never told us how hard life was for him having to pay the head tax and having to work long hours while growing up in the laundry business, we all experienced the hard work, long hours and the anxieties and difficulties that go into running a family restaurant or store. We all had to do our share of work."

- Rita Tam, daughter of Hamme Chow Aue

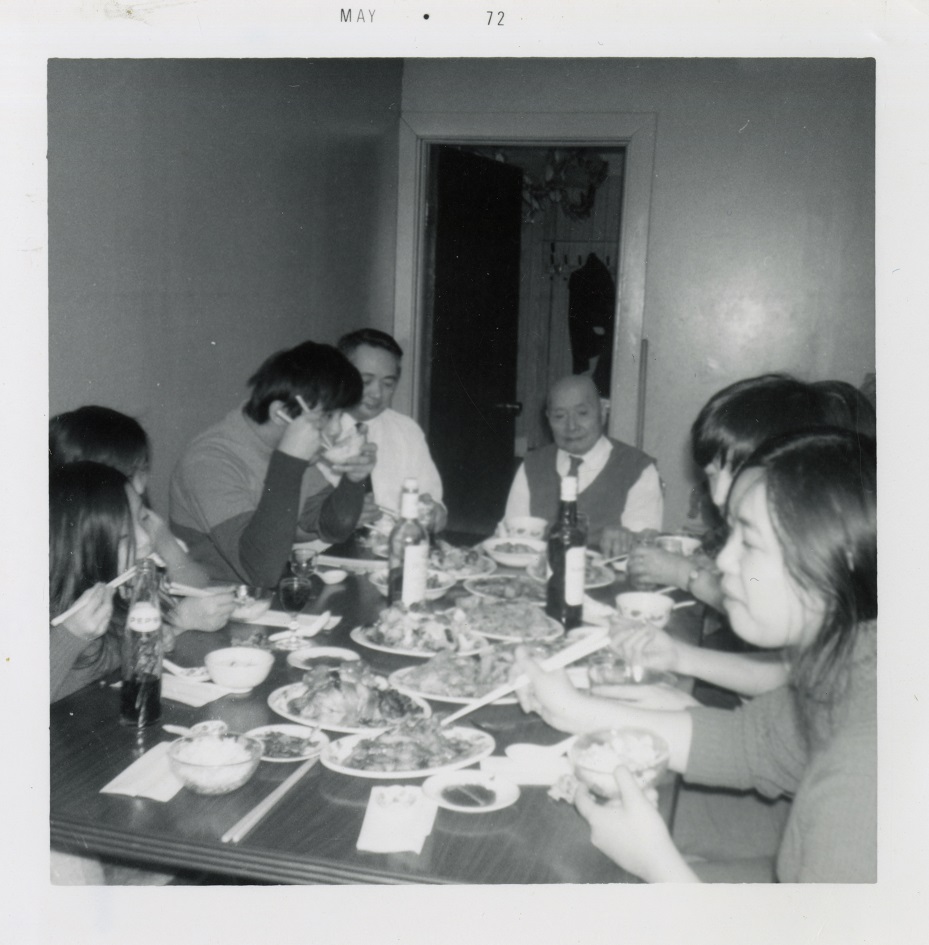

Aue family enjoying a family meal, May 1972. Courtesy of Rita Tam.

Aue family enjoying a family meal, May 1972. Courtesy of Rita Tam.

Hamme returned to China to marry Cow Jin Lee in 1947 (who changed her name to Carol Jean Aue, since she did not like the meaning of “cow” in English). Hamme often moved to other provinces in Canada for better opportunities to support his family. Finally, in 1954, the whole family travelled to St. John’s, eventually settling in Bell Island, Newfoundland. Over the following years, they ran two family-owned restaurant businesses and it was long, hard work. While Hamme was “an optimistic person, always looking ahead,” prejudice and anti-Asian racism existed. When closing the shop for the night, Rita was required to help watch while her father boarded up the windows to protect them from vandalism.

At times, Dad would call for my help and I would have to go, hoping that it would not be dark before I would arrive there. The main reason for my assistance was to have an extra pair of eyes to watch the cash register and the restaurant’s inventory so that nothing would get stolen or vandalized while Dad would go out to board up the large windows for the night. We were often taunted by the neighborhood boys who would often throw tomatoes or rotten eggs when Dad would go out to board the windows.”

- Rita Tam

Nevertheless, Hamme and Carol always placed a strong importance on family and community. They often were the first to help new immigrants adjust to life in their community in Newfoundland. After his retirement, in 1989, Hamme and Carol moved to Ontario. After a few years, they returned to Newfoundland, since he “treasured the smell of the salt air of St. John’s and the gusty wind blowing in his hair.” Many members of his family remained in Ontario. Today, the children and grandchildren of Sum Aue and Hamme Chow Aue have lived in Markham for over 30 years. York Region and Markham has a number of Newfoundlanders of Chinese descent who now call this region home.

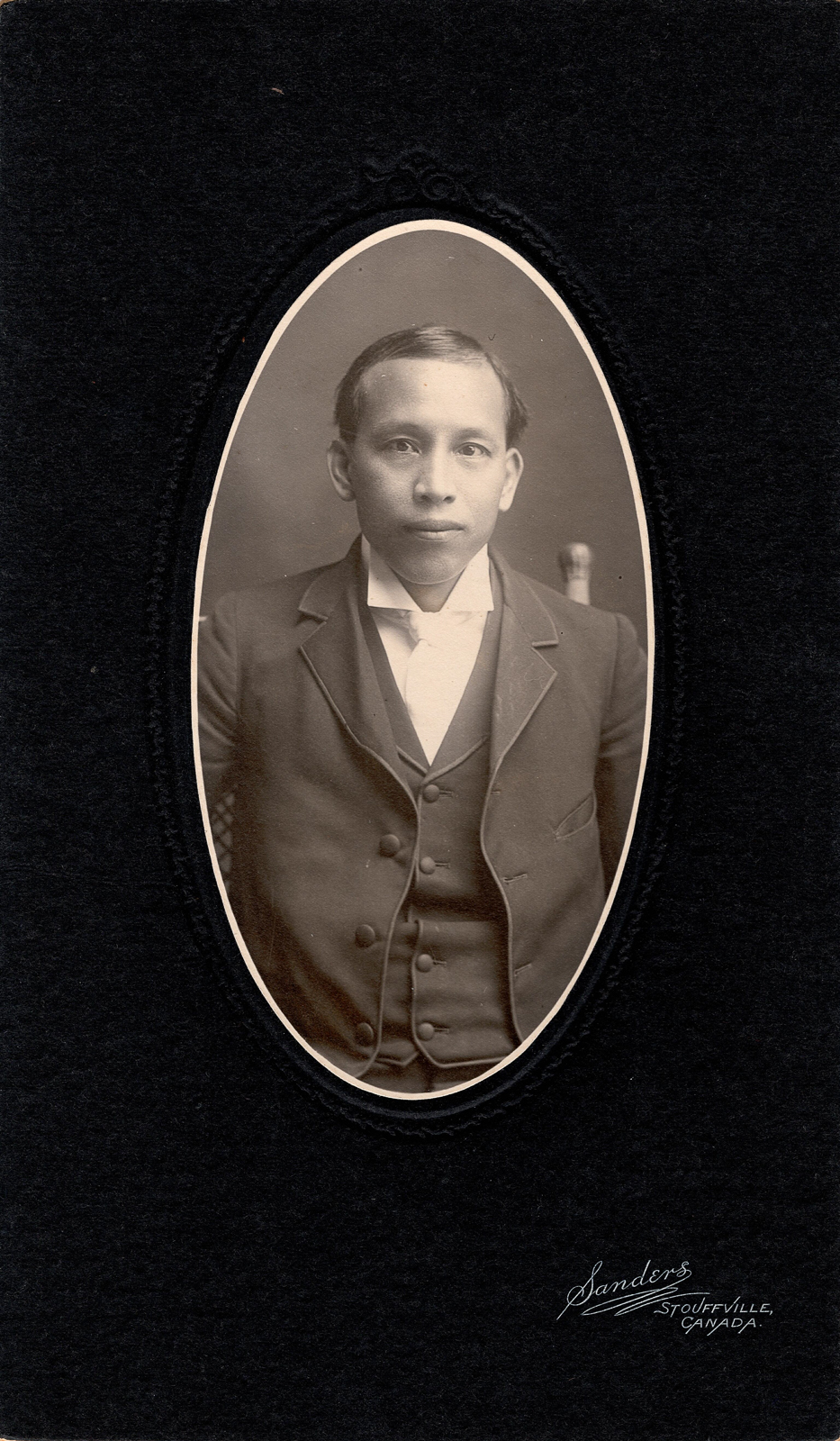

Newfoundland head tax certificates did not have a photograph attached, compared to the Canadian C.I. 9 certificates. This photograph of Hamme Aue is from his temporary travelling certificate which was issued in 1946 by the Consulate of the Republic of China in Toronto.

History of Chinese Canadians in York Region

After the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, many Chinese workers decided to move from Vancouver to other parts of Canada. There were few jobs available to them in British Columbia and there was strong resistance to Chinese workers in Vancouver by white Canadians.

Unfortunately, in every province they relocated to, they faced similar discrimination. Many of the locals were intolerant of the Chinese workers who spoke a different language and whose cultural practices seemed so foreign.

Many Chinese Canadians found work by setting up hand laundries, soaking, scrubbing, and ironing their customers’ clothes, bedding and table linens. Working in a hand laundry was hard physical work often done in cramped conditions.

Chinese laundries established between 1890-1950 were found throughout Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador. Chinese laundries were established in Toronto and neighbouring towns such as Markham, Aurora, Stouffville and as far north as Sutton. Take a look below at some of the Main Street street views that show the existence of Chinese laundries in York Region towns and villages.

Photograph of Yonge Street in Aurora around 1900-1901. The Chinese laundry owned by Chong Kee is on the middle right, beside the telephone pole. Originally owned by Fong Toy, it was sold in 1900 to Chong Kee. Unfortunately, the business was not profitable and business records reveal it was closed and sold to clear his debts in 1901. Photo Credit: Markham Museum (Gift of Kenneth and Roberta Hastings), c. 1901. Artifact Number: M.1975.94.19.

Photograph of Yonge Street in Aurora around 1900-1901. The Chinese laundry owned by Chong Kee is on the middle right, beside the telephone pole. Originally owned by Fong Toy, it was sold in 1900 to Chong Kee. Unfortunately, the business was not profitable and business records reveal it was closed and sold to clear his debts in 1901. Photo Credit: Markham Museum (Gift of Kenneth and Roberta Hastings), c. 1901. Artifact Number: M.1975.94.19.

The red brick building on the right, beside the IGA, is Law Sum’s Laundry. The hand laundry on Wellington Street, just east of Yonge Street, was owned and operated by Law Sum from 1916-1930. Due to the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act, Law Sum wasn’t able to bring his family from China to join him in Canada. Photo Credit: Aurora Museum & Archives, 1961. Artifact Number: 2002.19.256.

The red brick building on the right, beside the IGA, is Law Sum’s Laundry. The hand laundry on Wellington Street, just east of Yonge Street, was owned and operated by Law Sum from 1916-1930. Due to the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act, Law Sum wasn’t able to bring his family from China to join him in Canada. Photo Credit: Aurora Museum & Archives, 1961. Artifact Number: 2002.19.256.

On the right hand side of this photograph, is the sign "Mer Ming Laundry." Based on newspaper records and other photograph records, Mar Wing operated this Chinese laundry on Sutton's High Street as early as 1908. This building was torn down and replaced in the 1950s. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Georgina Pioneer Village & Archives, 1920.

On the right hand side of this photograph, is the sign "Mer Ming Laundry." Based on newspaper records and other photograph records, Mar Wing operated this Chinese laundry on Sutton's High Street as early as 1908. This building was torn down and replaced in the 1950s. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Georgina Pioneer Village & Archives, 1920.

When the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1923, Chinese workers, who were primarily men, were unable to bring their wives and children to Canada. This created a bachelor society of Chinese men in Canada. Often men of Chinese heritage travelled back to China to marry and have children, but then returned to Canada to continue working to support their family that remained in China.

Mah Wat was the owner of a Chinese laundry in Stouffville from 1902 to 1916. He shared the building with Mr. Monkhouse, a tailor. When he left Stouffville in June 1916, he thanked his customers for their patronage and kindness in the local newspaper, the Stouffville Tribune. He sold his business to Hing Lee, who did not remain in Stouffville for long, abruptly leaving in 1918. A number of other Chinese launderers served the Stouffville community until the 1940s. The last known proprietor of a local Chinese laundry in Stouffville was Seto E. Yeebick. In August 1940 he closed the shop and moved to Port Perry, a result of declining business.

Like Mr. Yeebick experienced in Stouffville, a rise in technology brought washing machines into homes, and removed the need for laundry services. Older Chinese men were unable to keep their doors open and many of the hand laundries closed. The Exclusion Act also stunted the growth of the Chinese Canadian community. Chinatowns across Canada had a very large number of Chinese men, with few women or children part of the community.

The War Years

Although as many as 300 Chinese Canadians served in the First World War, Canadian laws became more oppressive following the war. The Second World War proved to be a pivotal moment for many Chinese Canadians. Even before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, many cities in China were invaded and occupied by Japanese forces. Since the Chinese Exclusion Act kept many women and children in China, men in Canada were unable to make contact with their loved ones in the Japanese-occupied territory. Here in Canada, men and women actively responded through charitable fundraising drives to support their families back in China. Chinese Canadians heavily supported the Canadian Victory Loan Drive and the Red Cross.

During the Second World War, Chinese Canadians still didn’t have the right to vote. The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect, which was conflicting for many. They wanted to support Canada in the war effort, but also wanted to be treated equally. The Canadian government was reluctant to call up Chinese Canadians and many were turned away and barred from enlisting. Gradually restrictions were lifted as the need for soldiers grew as the war prolonged. Overall, over 600 Chinese Canadians served in the military, both in Canada and overseas.

Chinese Victory Celebrations, parade on Elizabeth Street. 26 August 1945. City of Toronto Archives.

Chinese Victory Celebrations, parade on Elizabeth Street. 26 August 1945. City of Toronto Archives.

Following the participation of Chinese Canadians in the Second World War, the need to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act intensified. Torontonian lawyers and The Queen’s Own Rifles reservists, Dock Yip and Irving Himel, met during the War. These two men led the advocacy campaign to repeal the Chinese Immigration Act.

Battle of Hong Kong

The first Canadian Army unit to engage in combat during the Second World War was during the Battle of Hong Kong in 1941. The Canadian Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers joined troops from Britain, India, Singapore, and Hong Kong to defend the port from Japanese invasion. They were not successful. Over 550 Canadian soldiers were killed or wounded and many others were taken as prisoners of war.

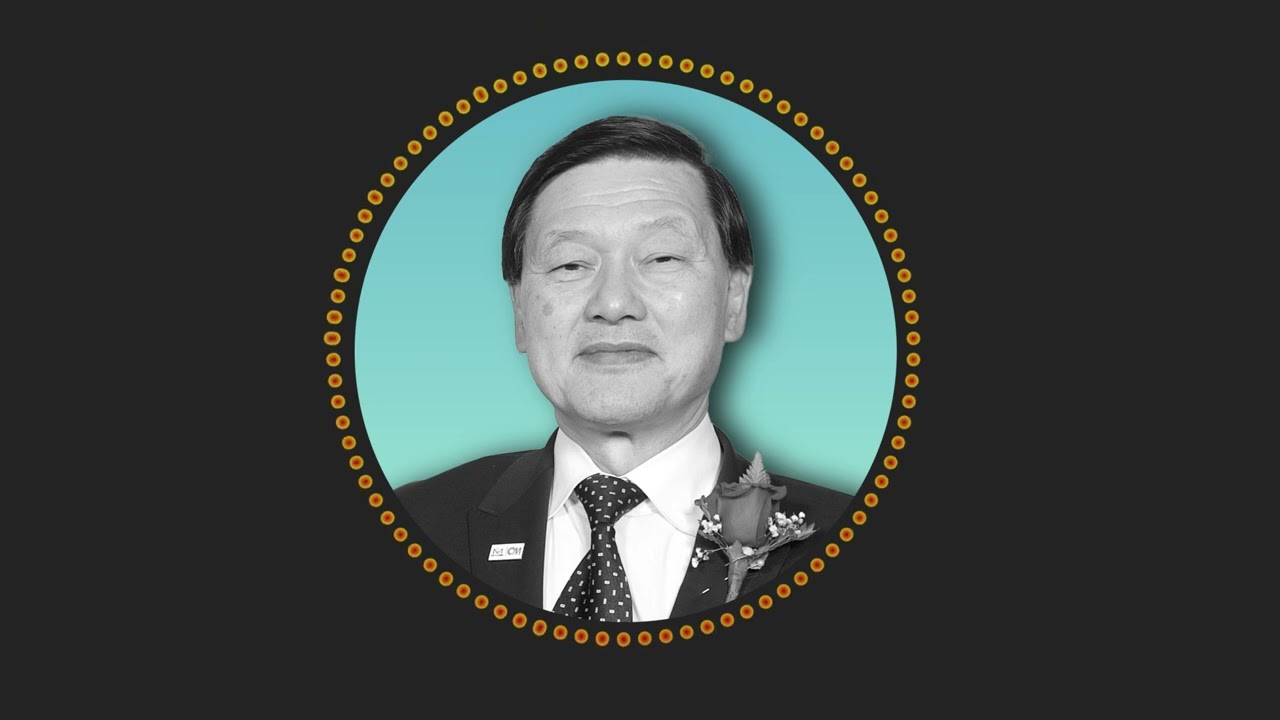

Today, many Chinese Canadians recognize their sacrifices through memorials and during Remembrance Day services throughout York Region. In 2012, given the numerous residents from Richmond Hill who immigrated from Hong Kong, then Richmond Hill City Councillor Godwin Chan passed a motion to formally recognize Hong Kong veterans who fought courageously during the Second World War. Similarly, a commemorative ceremony is held annually at the Markham cenotaph.

Deputy Mayor Godwin Chan with the plaque recognizing the Canadians who served during the Battle of Hong Kong, Richmond Hill Cenotaph (Located on Yonge Street, just north of Major Mackenzie Drive, the Cenotaph sits in front of the former Lillian McConaghy Public School/McConaghy Seniors Centre)

Deputy Mayor Godwin Chan with the plaque recognizing the Canadians who served during the Battle of Hong Kong, Richmond Hill Cenotaph (Located on Yonge Street, just north of Major Mackenzie Drive, the Cenotaph sits in front of the former Lillian McConaghy Public School/McConaghy Seniors Centre)

The importance of Chinese Canadians' contributions in the Second World War for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act were significant. Listen to Regional Councillor Alan Ho talk about the connections between the Second World War and the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Kew Dock Yip

Kew Dock Yip (葉求鐸) was a community leader in Toronto’s Chinatown and the first lawyer of Chinese descent in Canada. He played a pivotal role in the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and established the “Committee for the Repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act” with his friend and fellow lawyer, Irving Himel. They met while serving together in the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada regiment during the Second World War. They lobbied to remove entrance barriers for Chinese immigrants.

Watch this short trailer by the Queen's Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum on The Dock Yip Story, with interviews by his son, John Yip and historian Arlene Chan.

Mr. Yip served the Chinese community in Toronto for over 50 years as an advocate, a lawyer, and a Toronto School Board trustee. Today, his sons and grandchildren live and work in Markham and the Greater Toronto Area and continue to celebrate Dock Yip’s contributions to a more equitable society.

I remember many times, when he would get up early in the morning and go to the bus station and take the Grey Coach up to some small Ontario town to conduct legal business. The Chinese could not afford to close down their restaurants even for a day, so Dad would take the bus and go to them. It took so long to travel that often this was the only legal matter that he accomplished on that day.”

- John Yip, third son of K. Dock Yip

After the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1947, there still remained institutional barriers to immigration. So while the Exclusion Act was repealed, it wasn’t until Canada changed its immigration restrictions on race and national origin in 1967 that Chinese immigrants could apply for entry. Finally, after decades of national restrictions, family reunification could take place.

A delegation traveled to Ottawa to meet with Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to advocate for the revision of discriminatory immigration laws. Seated at the table are Foon Sien Wong, PM John Diefenbaker and the only woman in the delegation, Jean Lumb. Courtesy of Yip family, 1957.

A delegation traveled to Ottawa to meet with Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to advocate for the revision of discriminatory immigration laws. Seated at the table are Foon Sien Wong, PM John Diefenbaker and the only woman in the delegation, Jean Lumb. Courtesy of Yip family, 1957.

Additional changes to Canadian immigration laws led to an influx of immigrants from Asia in the 1980s. Areas such as Toronto, Scarborough, Markham and Richmond Hill became popular locations for new arrivals. In the 1990s, many new arrivals came to Markham and Richmond Hill from Hong Kong, given the imminent handover of the British colony to the People’s Republic of China. In the years following 1997, immigration patterns shifted and York Region saw a sharp increase in the number of immigrants from Mainland China.

During and even after the repeal of the Exclusion Act, cultural differences and discrimination often kept Chinese Canadians isolated. To provide support and community, leaders of the Chinese communities created religious, political and charitable associations across Canada. Kinship is an important aspect of Chinese culture. The benevolent associations provided opportunities for the bachelor society of men to find safe companionship, camaraderie and support settlement. Ontario clan and district associations first established in Toronto’s Chinatown. In 1982, the not-for-profit Federation of Chinese Canadians in Markham (F.C.C.M.) was established to provide support services for the Chinese community in Markham. Dr. Ken Ng believes in creating a strong community where we all can feel accepted and find a place of belonging.

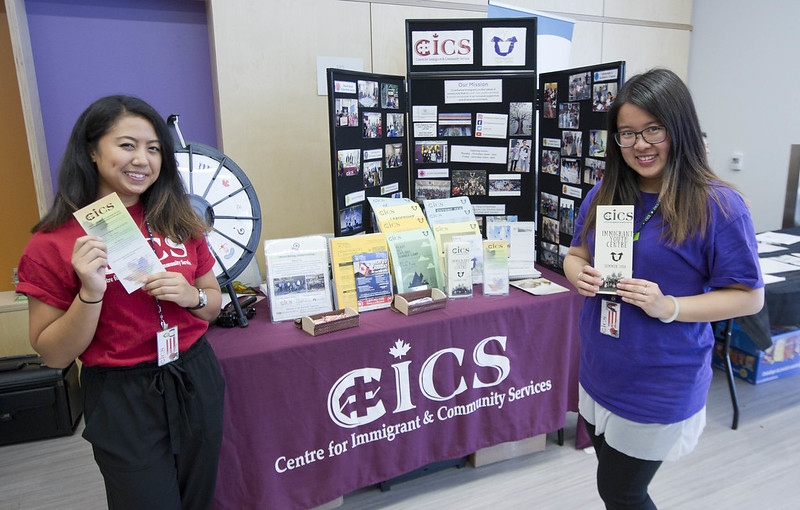

Welcome Centres are important to building connections for new immigrants to Canada. Speaking from her own experiences, Lily Liang talks to the importance of making connections within the community. Listen to Lily speak from her perspective on the importance of settlement agencies within York Region. Educator Jadas Lau provides this compassionate perspective on the importance of helping new immigrants, to build better relationships and community.

Just one of many community support organizations for newcomers. The Centre for Immigrant & Community Services hosted a table at the Aaniin Grand Opening 2018 Celebration. Courtesy City of Markham.

Just one of many community support organizations for newcomers. The Centre for Immigrant & Community Services hosted a table at the Aaniin Grand Opening 2018 Celebration. Courtesy City of Markham.

I know it's very intimidating: welcome centers, particularly for immigrants. Because the majority of [people are] speaking English, but the centers are there to help immigrants to learn like English, to integrate, to find a job and such, and also to find community members. Because it gets very lonely and very hard, particularly because you're starting very, very fresh and everything that you knew was like not familiar anymore.

- Lily Liang

Some YRDSB students come to Canada as International Students. Listen to former YRDSB student Hanjia Li speak about her experiences getting settled in York Region as a student. She also talks about the differences between the living in the community as an International Student, compared to a Permanent Resident. Listen to the audio clips below to find out more:

Throughout York Region, many members of the Chinese diaspora community have interesting and different pathways to York Region. Listen to some of these voices below: